Over 15 years ago I studied a local Christian right campaign against gay/lesbian rights in the Pacific Northwest for my book The Stranger Next Door. I spent a year interviewing people in a small timber community to try to understand why the issue of sexuality emerged there. They were white working and middle class people, mainly evangelical Christians.

Over 15 years ago I studied a local Christian right campaign against gay/lesbian rights in the Pacific Northwest for my book The Stranger Next Door. I spent a year interviewing people in a small timber community to try to understand why the issue of sexuality emerged there. They were white working and middle class people, mainly evangelical Christians.

I met people who believed gays and lesbians are sexual predators who were out to convert their children. Who considered teachers to be untrustworthy representatives of the liberal secular humanism, who were destroying the family. Who believed that multiculturalism is a bad word. And who saw themselves as victims. They felt that their power as Christians, small town Americans, and as white people, was slipping away.

After the book was published, I moved to New Jersey and focused my attention on other things. I assumed the world of politicized Christian conservatism had become increasingly marginal, and largely irrelevant to Republican Party politics.

But then came the Trump campaign. Even though Trump did not run as a Christian conservative, his campaign, and the issues it raised, echoed many of the themes I saw in my research in small-town America. His slogan “Make America Great Again” was tailor made for those sectors of society who believe their power is slipping away, who long for the “good old days.” Trump’s election prompted me to revisit my research on the rightwing, to try to make sense of the political universe we are now dealing with.

The fact that Trump seemed, at least during this campaign, like more of an opportunist than an ideologue fooled many of us. He may be an opportunist, but he has surrounded himself with ideologues, a governing coalition that reaches across the spectrum of the American right. It is an unstable coalition, as we’ve seen from the leaks coming out of the White House. But it is a ruling coalition that brings together different sectors of the rightwing. And it is important for us to understand it.

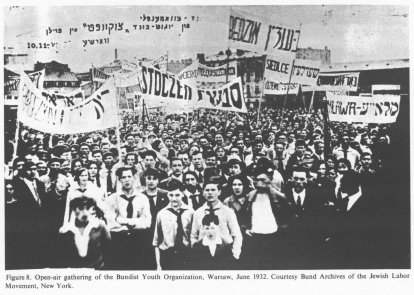

Analysts often divide the American rightwing into the Secular Right, Christian Right, and the Xenophobic Right. Collectively, the right stands for the reinforcement of racial, ethnic, class, gender, sexual hierarchies and the belief that these hierarchies are natural and/or God-given. But different hierarchies are of greater or lesser importance for different sectors of the American rightwing.

The secular right is mainly concerned with relationship between state and economy. It wants to unleash capitalism and minimize government regulation. The Christian right concerns itself with the relationship between church and state. It wants to fight against what it sees as the secularization of American culture. And the xenophobic/far right concerned primarily with preserving whiteness and national dominance. All sectors champion male dominance and white/Christian supremacy. Some do so very explicitly, others in coded ways.

Until now, the Republican Party has mainly drawn its leadership from the secular right. The Christian right has been a powerful presence during the past few decades, but mainly at the local and state level. And it has distanced itself from the xenophobic right, at least publicly. Trump is changing all of that.

Trump, the presidential candidate, was basically a “paleoconservative.” He adhered to nationalism, free markets, and moral traditionalism. He supported a strident form of anti-immigrant politics, an isolationist foreign policy, and a deep skepticism toward economic globalization that put him at odds with an important element of the business agenda.

Trump, the president, has assembled an administration comprised of a coalition of the secular, Christian and xenophobic right. Some say it is the widest rightwing coalition ever assembled by an American president. And it is far more radical than anyone would have believed after the election.

The Trump administration has welcomed Christian conservative influence (Betsy DeVos and Mike Pence). It has has placed white supremacists such as Steve Bannon—a former spokesperson for the so-called “alt-right.” That means that Islamophobia is likely to be central driver of foreign policy—hence the recent effort to implement a Muslim ban. For Trump’s different constituencies on the right, Islam is a perfect target, encapsulating beliefs in American and Christian superiority, evoking fears of terrorism, and playing into clash of civilizations-preservation of Christian nation; nationalism. It targets Jews in coded, less explicit ways.

In terms of Trump’s cabinet appointees, a Tea Party libertarianism is ascendant: a Secretary of Education who doesn’t believe in public education, a Secretary of State who believes that foreign policy should be run by Exxon, and so forth. They basically want to destroy the Federal Government. And despite all of Trump’s campaign talk about “draining the swamp” of crony capitalists, he has assembled a cabinet that is more pro-business than any other before it, and which includes Wall Street bankers and corporate globalists like Steve Mnuchin and Rex Tillerson.

I’ve heard some liberals reassure us, saying that in four years we will take back Congress and the Presidency. But that’s far too optimistic. The basic operations of our democracy are now under threat. What are we likely to see within the coming months? A massive attempt to roll back the last fifty years of liberal social reforms and an undermining of democratic institutions. The disruption and destruction of Federal government and privatization of many of its basic functions.

Will more moderate Republicans push back? Will mass mobilizations push Democrats to the left? Will apolitical Americans rise up when they realize they will lose their health insurance, and when they defund their kids’ schools? Or will they direct their wrath against the most vulnerable members of our society? The answer depends, in part, upon how quickly and effectively we can mobilize to defend the institutions that Trump is trying to destroy.

The Yale historian Tim Snyder, who has written extensively about the rise of fascism, says, “we have at most a year to defend the republic.” What we do in the next weeks and months is thus of vital importance.

(Thanks to http://blog.feministische-studien.de/2017/03/understanding-trumpism/)